Lying on opposite banks of the Mechi River, the Naxalbari block (of West Bengal) in eastern India and the Jhapa district of eastern Nepal are en route to the Mahananda-Kolabari-Mechi transboundary passage for elephants in the eastern Himalayan foothills. Both locations witness regular elephant incursions damaging properties and destroying crop fields. The latter is a matter of grave concern, especially for the smallholder farmers on both sides of the river.

When their paddy and maize crops ripen, the farmers spend nights guarding the crop from elephants. Traditionally, they would build makeshift elevated structures of bamboo or tarpaulin near their crop fields to serve as watchtowers. But these structures can barely withstand the often-turned-lethal human-elephant conflicts, not to mention the exposure to snake and insect bites.

The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) collaborated with the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) to construct six concrete-built watchtowers in the Naxalbari block to provide safe and durable vantage points to local farmers for guarding their crops. This endeavour took off with ICIMOD Director General, Pema Gyamtsho, officially launching the construction of a new watchtower on 4 October 2024.

The new watchtowers are an architectural novelty to these remote locations that are predominantly reliant on temporary polyethene, wood or bamboo structures to serve the purpose of (crop) surveillance. The new towers, in contrast, can provide additional facilities such as solar-powered LED lights, and emergency shelters (with kitchens and safe storage spaces) to the villagers during elephant raids, besides being sturdy and better-elevated observation towers vis-à-vis the temporary structures. Voluntary involvement of the villagers -be it in guarding the construction sites from vandalism or in helping to cure concrete structures for durability - during the construction of the new watchtowers spoke volumes of how strongly they felt the need for such facilities that can potentially provide more safety and security for lives, livelihoods and property.

In fact, local communities had strongly expressed the need for tenable solutions to manage the risks of human-elephant conflicts at the various consultation sessions co-organised by ICIMOD and ATREE for piloting strategies for human-elephant coexistence. In tandem, ICIMOD partnered with local authorities on both India and Nepal sides in initiatives to nudge changes in community attitudes and behaviour toward managing elephant incursions.

In the Naxalbari block, for instance, the local authorities complemented ICIMOD’s initiatives by installing solar irrigation pumps to encourage farmers into growing alternative crops less attractive to elephants, and by placing solar streetlights in the vulnerable settlements to reduce accidental human-elephant encounters. Three solar irrigation pump sets and 40 solar streetlights were installed with funding support from the Department of Water Resources Investigation and Development (DWRID), Government of West Bengal and the Naxalbari Block Development Office, respectively.

The local government also allocated funds for setting up market stalls where farmers can sell the alternative crops and launched habitat restoration projects. These efforts have encouraged many farmers to resume farming that they had stopped in apprehension of elephant raids.

Just across the Mechi river, farmers in Bahundangi village of the Jhapa district of Nepal can also harvest their crops without fearing heavy economic losses due to elephant encounters, now. Thanks to the seasonal fences installed with ICIMOD’s support. Simultaneously, ICIMOD has succeeded in fostering widespread awareness about human-elephant ‘co-existence’ through a range of initiatives starting from the inclusion of lessons on coexistence in school curriculum to supporting the Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) for managing human-elephant encounters so that the villagers can do away with hostile practices like using firecrackers to scare off elephants.

There is a positive perceptual change among the local communities – elephants are now treated as animals displaced by shrinking habitats and dwindling food sources, rather than as ‘incursors to be thwarted’. From a hotspot of human-elephant conflicts, Bahundangi is now Mechinagar municipality’s ‘model village’ of human-elephant coexistence.

With best practice cases like Naxalbari and Bahundangi on hand, ICIMOD is pursuing a holistic approach that pools together a combination of proactive initiatives such as, the construction of durable, multi-functional watchtowers, encouraging farmers in adopting crops less appealing to elephants, capacity building for human-wildlife sensitisation, advocacy and monitoring, leveraging government support, and nudging changes in community attitudes towards managing human-elephant encounters. These complementary actions are shaping up an ethos of human-wildlife coexistence along the Mechi River corridor of the eastern Himalayan foothills.

Air pollution remains one of the most persistent and pressing challenges in the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) region. The region is caught in a recurring cycle of toxic air, with pollution levels peaking twice a year, between October to November and from March to April. March–April pollution surge is largely driven by widespread forest fires, which have been increasing each year due to drier winters, creating a layer of tiny particles, obstructing the visibility called haze. This haze can be composed of various particles, including dust, smoke, aerosols, and smog. For the October–November period, the pollution spike is largely attributed to agricultural residue burning across the Indo Gangetic Plains (IGP) countries, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan, as farmers prepare their fields for the next cropping cycle. Although these burnings are localised, their effects are widespread, affecting the HKH region with adverse environmental, socio-economic, and health consequences.

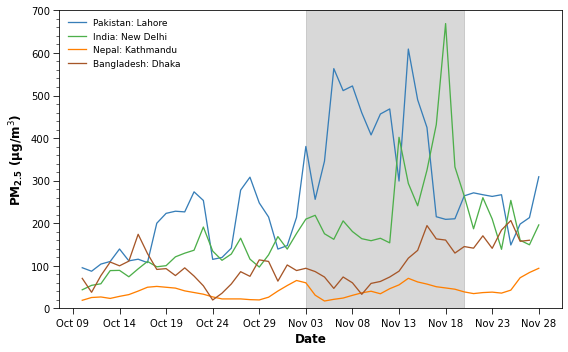

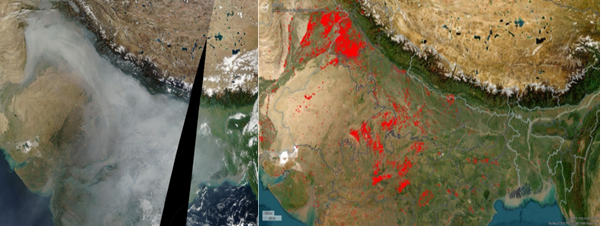

November 2024 recorded PM2.5 (particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometres or less) air pollutant concentrations exceeding 500 µg/m3 in Lahore, Pakistan, and New Delhi, India, as recorded by AirNow. Peak haze (slight obscuration of the lower atmosphere) and air pollution levels occurred in mid-November 2025, aligning with burning activity. The haze then moved eastward across the IGP, with rising PM2.5 concentrations in downstream cities. Dhaka, Bangladesh, recorded a noticeable rise in particulate pollution following November 12, indicating regional movement of the air pollutants. This spatial and temporal pattern confirms that the agricultural residue-driven haze events contribute to air pollution across the IGP region.

From the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) satellite imaging data, we can see how the haze over the region decreases as the crop burning period ends. In early November 2025, satellite data captured a thick haze spreading across the IGP. Between November 4 and 7, over 1,250 active fires were recorded, indicating widespread agricultural residue burning. The haze persisted through the month, peaking in intensity toward the end of November. Although cloud cover briefly masked the smoke in NASA imagery, the haze became visible again by the first week of December. As fire activity declined to just under 200 counts, visibility improved noticeably.

The pattern tells a clear story: more stubble (agricultural residue) burning leads to heavier haze. The data reinforce what is increasingly evident: agricultural fires are a major contributor to regional air pollution, with serious consequences for health and the environment.

In the broader context of climate change and air pollution impacts, it is unfair to highlight agricultural residue burning without acknowledging pollution from road traffic and industries. However, the challenge of agricultural residue burning persists and remains a significant contributor to air pollution. While its impact may be smaller compared to other sources, it is an issue that can be addressed through coordinated efforts involving the government, the private sector, and farmers.

Unfortunately, discussions on agricultural residue burning, air pollution, and health impacts often overlook the struggles of farmers. Farmers' continued reliance on burning stubble, particularly in the IGP, is driven by a complex interplay of cultural norms, economic constraints, labour shortages, and tight timelines between crop cycles. The practice of burning is perceived as a quick and cost-effective way to clear large volumes of agricultural residues for the next crop season. In most parts of the IGP, wheat is planted right after rice is harvested, within approximately 20 days.

Stubble burning persists due to several challenges, including limited awareness among farmers about its environmental and health impacts, and the widespread myth that burning returns nutrients to the soil. While subsidies exist, tools like straw choppers and balers remain costly and out of reach for many small-scale farmers. Weak market linkages for stubble, especially paddy straw, further reduce motivation for sustainable management. The transitions to alternatives for agricultural residue burning remain hindered by inadequate and fragmented policy support, particularly limited financial incentives and weak market development are making adoption difficult for farmers and stakeholders.

There are promising solutions, such as affordable residue management technologies to policy innovations and community-led initiatives that are showing real potential to reduce stubble burning and improve air quality.

The innovative approach of turning agricultural residue into pellets is emerging as an ambitious alternative to burning fossil fuels, creating more green jobs, improving soil health and air quality, and a home-grown economy resulting in lesser dependency on fossil fuel imports. Converting the paddy stubble into high-density pellets reduces agricultural residue burning and helps in combating the associated air pollution by substituting fossil fuel in the industries, which further thrives the clean and green environment. The integration of agricultural residues into the energy matrix can enhance energy security and diversification of energy sources. As global energy demands increase, the reliance on traditional energy sources can pose risks to energy security.

While pelletisation is promising, there are challenges, such as transportation and storage costs, and availability of pelletisation facilities. Besides, only a handful of machinery is deployed at available pelletisation facilities, so not all farmers have access to such machinery. These factors contribute to farmers' hesitation to adopt pelleting, despite awareness.

There are also other sustainable agricultural residue management practices where agricultural residues are left in the field to naturally decompose, which improves soil health and fertility over time. Unlike burning, this approach reduces environmental pollution and enhances productivity through methods like mulching, no-till farming, and crop rotation. This approach is encouraged as studies show they can boost cereal grain yields by up to 37% and significantly cut soil erosion and carbon emissions. However, adoption remains limited due to low farmer awareness, lack of machinery access, and competing uses for residues such as livestock fodder.

Biochar is the other promising ex-situ solution for managing agricultural residue, where biomass residue is converted into carbon-rich materials to use as fertiliser in the field. This addresses the residue disposal issue while improving soil fertility, productivity, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Studies show biochar can increase average yields by 11% and cut 12% of human-induced emissions annually. However, high production costs and variable performance limit widespread adoption. Collaborations with research institutions and international bodies, along with strong policy support, are essential to improve production standards, build capacity, and make biochar a viable tool for sustainable agriculture and climate action.

Scaling up the agricultural residue management solutions will require government support to get them off the ground. The issue of low supply of the paddy straw stubble used in the productive sector is addressed through the awareness and capacity building of farmers, but the effort is insufficient. Thus, IGP countries' strict regulations, such as mandatory enforcement of agro residue-based biomass pellets in the co-firing, and 7–20% use in thermal power plants and brick kilns could advance the scaling up of pelletisation. This enforcement would create significant market demand for the paddy straw pellets, attracting interested investors to get engaged in the paddy straw-based pellet production.

Managing agricultural residue needs to be heavily subsidised to offset related costs. Countries in the IGP are increasingly opting for strict rules to control open agricultural residue burning. In India, the open burning of agricultural residue can be reported as a crime. With farmers facing threats of fines and imprisonment, it has become almost impossible to engage in constructive dialogue, and it has further alienated the farming community. A more effective approach to rewarding farmers for not burning agricultural residue can foster collaboration and cooperation.

Control agricultural residue burning and solving the smog and haze problem will require putting farmers at the centre of the conversation. Innovation and policy commitment, along with strong monitoring tools, are the keys to cleaner air and a healthier environment.

Understanding and addressing farmers’ challenges is only the beginning. The available solutions are showing promise in addressing the current haze crisis, but these are not standalone or long-term solutions. The need to invest in research and development to explore more sustainable alternatives is ever pressing. Long-term solutions must address the cause, and not just manage symptoms.

The World Meteorological Organisation’s (WMO) State of the Climate in Asia 2024 report predicts worsening repercussions of climate extremes in Asia, warming twice as fast as the global average. The findings of the report corroborate ICIMOD’s 2025 HKH Snow Update and 2025 Monsoon Outlook, both forecasting escalating likelihood of (water-related) calamities for the Hindu Kush Himalayan (HKH) region of Asia, in particular.

Continent ‘hit hard by rising temperatures and extreme weather’, states the United Nations’ authority on climate, weather, and water, as weather extremes ranging from prolonged heatwaves, and droughts, to rain cause “havoc”, “heavy casualties”, “destruction” and “heavy economic and agricultural losses” across the continent.

While floods in Asia in 2024 were among the most severe precipitation-related events recorded since 1949, 4.8 million people were affected by drought in China in 2024, Myanmar set a new temperature record of 48.2ºC, and the Urumqi Glacier No.1 in China’s Eastern Tian Shan recorded most negative mass balance since records began in 1959, among other calamities.

In the HKH region, 23 out of 24 High Mountain Asia glaciers show continued mass loss. Reduced winter snowfall and extreme summer heat intensified losses in most of Nepal, Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) in China and Sikkim in India, among other high-altitude areas in the central Himalayas.

The WMO report finds a belt of below-average snow cover extent (SCE) from western to eastern parts of Asia, with negative SCE anomalies dominating the central and the middle Himalayas in 2024. In tandem, ICIMOD’s 2025 HKH Snow Update, finds November 2024 – March 2025 to be the vicennial-record-low snow season in the HKH with a snow persistence of -23.6%, besides being the third consecutive year of negative snow anomaly in the region. Persisting and alarming extents of anomalies are observed in river basins like Mekong (-51.9%), Brahmaputra (-27.9%), Yangtze (-26.3%), Ganges (-24.1%), Amu Darya (-18.8%), Indus (-16.0%), where seasonal snow melts are crucial for agriculture, hydropower generation and other critical ecosystem services.

Sher Muhammad, Remote Sensing Specialist at ICIMOD says, “These observations largely coincide with what is being seen across the HKH region as well. Seasonal snowmelt contributes approximately 25 % of annual river flows on average across the HKH, rising even higher in western basins—yet continual snow deficits are eroding this critical source, triggering early-summer water shortages, heat stress, and worry among downstream communities.”

This is worrying news for countries like China and Afghanistan, already exposed to long-term water stress and droughts conditions. According to the WMO report, in 2024 Western and south-western Afghanistan saw more frequent sand and dust storms than average, possibly linked to long-term drought conditions. On the other hand, the Yunnan and southern Sichuan Provinces in China experienced both winter and spring droughts, while in August 2024, drought intensified in Sichuan, the Yangtze River, and Chongqing – leading to economic losses of 2.89 billion Yuan. Persistently below-normal precipitation being a key driver of these droughts.

While WMO reports considerable variation in precipitation anomalies in 2024 - Pakistan’s southwestern province of Balochistan and Myanmar’s Irrawaddy delta experiencing above-normal rainfall vis-à-vis China’s Altyn-Tagh and Kunlun Mountains between the Tibetan Plateau and the Tarim Basin, along with Pakistan’s western Himalayas and Afghanistan’s Hindu Kush mountains recording below-normal precipitations – ICIMOD’s 2025 Monsoon Outlook predicts a wetter and hotter summer monsoon between June and September 2025 for most of the HKH countries, with the 2024 hotspots of rainfall anomalies, as identified in the WMO report, remaining unchanged.

Nepal, for instance, that saw incidents of mudslides, waterlogging and sedimentation, and faced significant damages and economic losses due to excess rainfall in 2024, is again likely to receive above-average rainfall this year, along with India, China’s TAR and most of Pakistan (a country also imperiled by precipitation-induced floods in 2024). On the other hand, among countries / areas predicted to experience below average rainfall is the already drought-affected Afghanistan with severe dryness likely to persist in its western parts.

Simultaneously, the Monsoon Outlook predicts temperature anomalies in South Asia, including the HKH, to range between 0.5⁰ and 2⁰C above the long term-average, during June - September 2025. This prediction comes on the back of WMO’s report of frequent incidents of heatwave outbreaks across China, India and Myanmar in 2024, alongside sea-surface temperature rise in Asia at nearly double the global mean rate.

With the findings from all these reports pointing to the ever-heightening propensity of climate extremes and catastrophes in the HKH region under the irreversible effects of accelerating climate change, anticipatory lifesaving and support actions are the need of the hour. Work of national meteorological and hydrological services and their partners is becoming “more important than ever”, states WMO Secretary General, Professor Celeste Saulo, in this context.

According to Saswata Sanyal, Disaster Risk Reduction Lead, “The WMO report rightly emphasises the urgent need for anticipatory action in the face of escalating climate-induced disasters. This proactive approach is crucial for anticipating and mitigating disaster impacts before they fully unfold. ICIMOD recently joined the Intergovernmental Organizations' Cooperation on Anticipatory Action to further 'acting ahead of a predicted hazardous event to prevent or reduce impacts on lives and livelihoods and humanitarian needs' across HKH. This will directly empower communities to take necessary actions against the increasing threats of heavy rainfall, flash floods, and other water-related hazards in the region.”

Reminiscing the devastating impact of the 2024 monsoon floods on the communities from Kathmandu to the floodplains in Terai, Neera Shrestha Pradhan, Cryosphere and Water Lead at ICIMOD, highlights ICIMOD’s proactive moves towards strengthening anticipatory actions, “ICIMOD is contributing to the global EW4All initiative, aligning with its four pillars—ranging from investing in nature-based solutions to mitigating flood impacts, to ensuring localised and community-based responses. Recognising that early warning alone is not enough, ICIMOD is working to strengthen anticipatory early action and preparedness by fostering collaboration between communities and local governments. We are also working with partners to pilot gamification of training approaches — making learning more interactive, and impactful. These efforts aim to build lasting resilience in the face of increasing flood events and multi-hazard risks in our region.”

WMO’s State of the Climate in Asia 2024 coincides with 2025 Bonn Climate Change Conference (SB62), a crucial mid-year meeting for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), from June 16 to June 26 in Bonn, Germany. This is a preparatory event for the upcoming COP30 in Belém, Brazil, with particular emphasis on adaptation and setting the agenda for COP30.

Read the full press release here: https://www.icimod.org/press-release/state-of-the-climate-in-asia-2024-icimod-response-to-wmo-flagship-report/

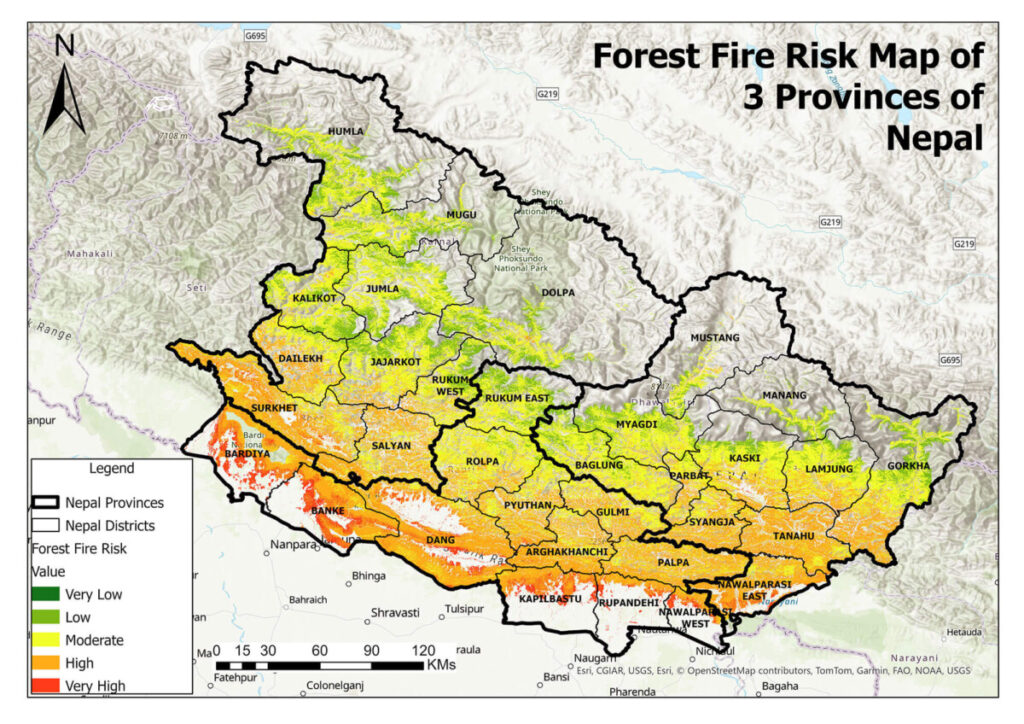

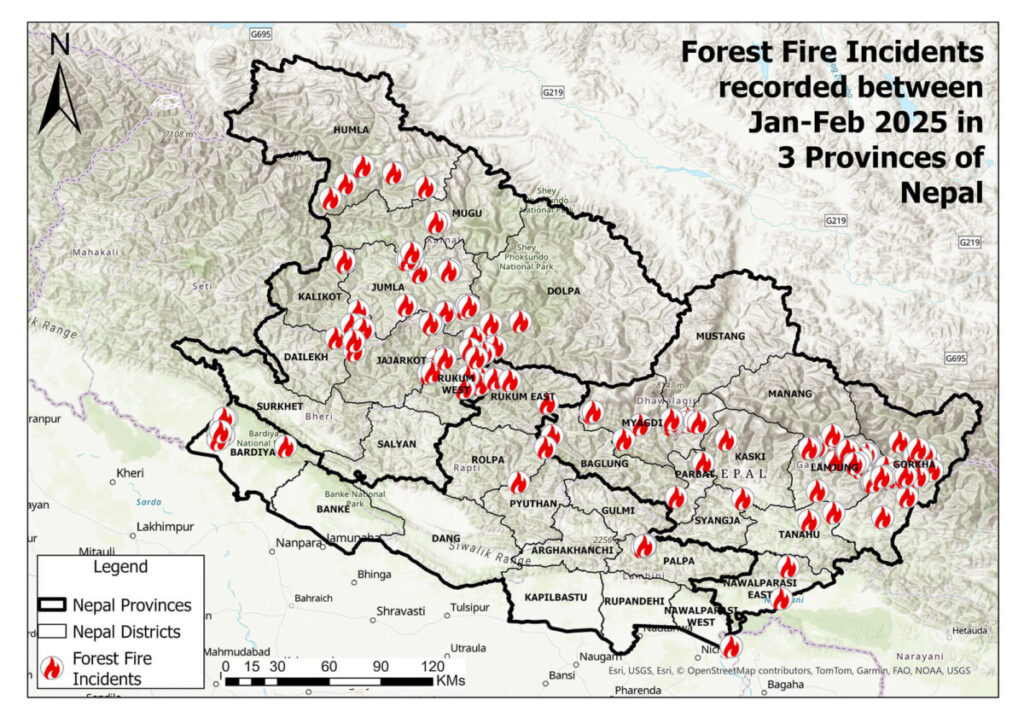

The Forest Fire Detection and Monitoring System (FFDMS) of the Nepal Government’s Ministry of Forest and Environment, detected around 1300 forest fire cases in the country just in a month-long span between 5 March and 5April. However, the number of daily forest fire outbreaks saw sudden spikes since 21March, albeit with some day-to-day fluctuations (Figure 1).

Simultaneously, a rapid assessment of the air quality data obtained from the Khumaltar air quality monitoring station in Lalitpur during this one-month period, revealed severe deterioration in air quality between March 21 and April 5 with levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) altering from 35–170 μgm-3 and carbon monoxide (CO) concentrations ranging from 0.3–1.5 ppm; this is vis-à-vis the situation between 5-20 March (both PM2.5 and CO levels showing lower variability , ranging between 40 - 85 μgm-3 and 0.4 - 0.6 ppm, respectively) (Fig 2, left panel).

The mean PM2.5 concentration for 21 March - 5 April was measured at 97.2 µgm-³, almost 1.5 times higher than the measured value of 65.9 µgm-³ for 5 March - 20 March. The mean CO concentration, on the other hand, was measured at 0.8 ppm for 21 March - 5 April , almost 60 percent higher than the mean value (0.5 ppm) for the preceding fifteen days. (Fig 2, right panel). Such high levels of concentration of pollutants, PM2.5 in particular, increase the risk of cardiopulmonary diseases as well as all-cause mortality.

While the US Government’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) MODIS satellite images corroborated with the drastic change in the forest fire situation between 21 March and 5 April with fire incidents being more prevalent over time and space, it also revealed higher spatial concentration of the fire hotspots in the western/southwestern side of the Kathmandu valley (Figure 3)).

To be noted in this context, that nearly 26% outbreaks were detected in the Madesh province, 25% in Bagmati, 16% in Koshi, 14% in Lumbini and 18% cumulatively in the Gandaki, Karnali, and Sudurpashchim provinces, respectively.

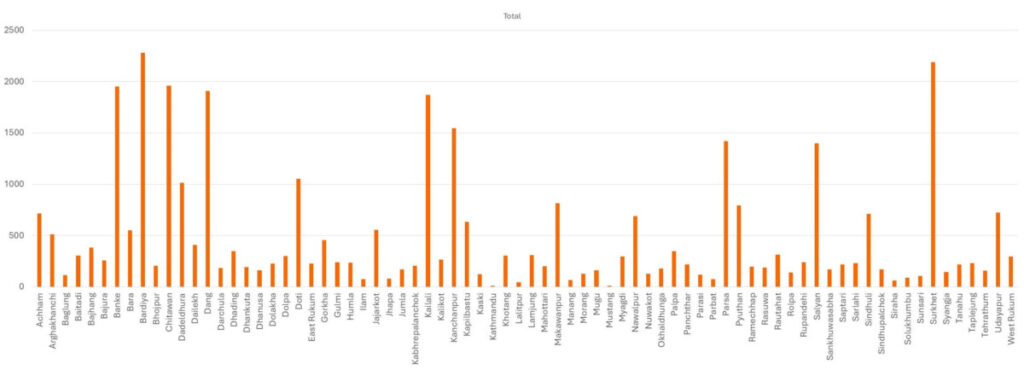

The FFDMS data, on the other hand, shows only one localised case of forest fire in the valley (at Lalitpur) itself during this month-long phase, while several major fire hotspots – for instance, Chitawan (147 events), Makawanpur (110 events), Sindhuli (49 events) in the Bagmati province itself, or Parsa (174), Udayapur (77), Dang (54), in the adjacent Madhesh, Koshi, and Lumbini provinces, respectively - were detected at over 100 kilometres away from the valley.

With smoke plumes often rising to 4000-5000 metres, way beyond the typical planetary boundary layer in the region, forest fires are known for increasing the chances of long-range transport of emissions like carbon monoxide (CO), fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone precursors.

But how does the transport and dispersion of the pollutants occur? Empirical analysis of the process is relatively scare. Thus, to get an empirical perspective of it, especially during this year’s coinciding phase of severe air pollution in the Kathmandu valley and raging forest fire outbreaks across Nepal, we used the Khumaltar station as our receptor location for monitoring the source, transport and dispersion of pollutants in the local air1.

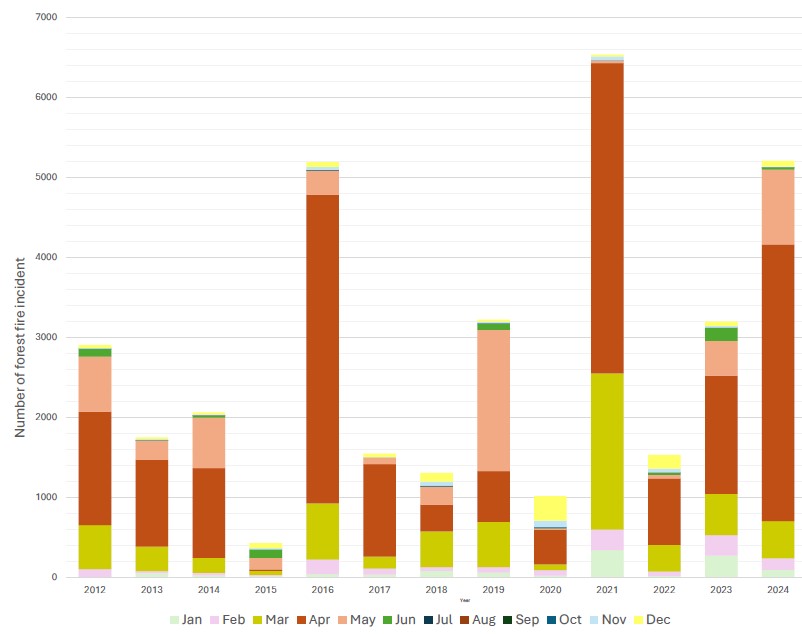

Forest fires from dried vegetations usually intensify during the pre-monsoon months in the southern Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) foothills (of India, Nepal and Bhutan) as well as at higher altitudes close to the cryosphere, due to dry weather conditions extending through the winter season. With longer spells of dry weather conditions becoming common in the region under the exacerbating effects of climate change, forest fires also have amplified in frequency, scale and intensity over the past ten years or so.

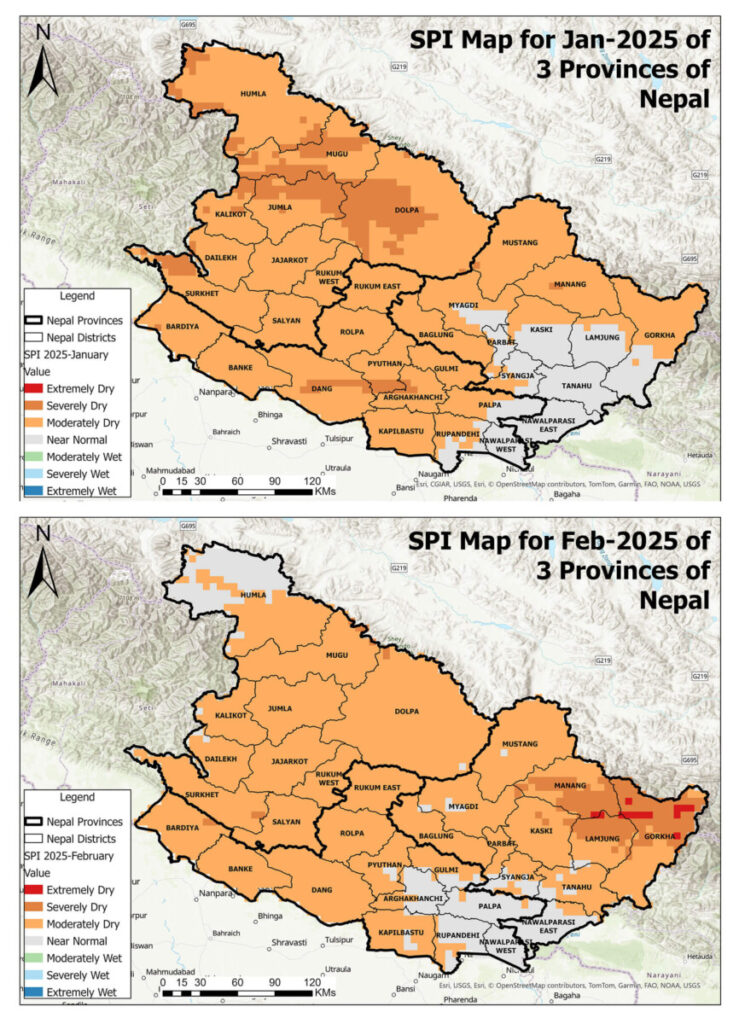

This years’ fierce pre-monsoon forest fires in Nepal, for instance, came on the heels of a drier-than-normal winter season - Nepal received only nine per cent of the average winter rainfall by 23 January , 2025, and the HKH region, in general, saw record-low winter snowpack this winter – and an advanced drought warning from the National Agricultural Drought Watch.

But it is the local meteorological condition, such as wind direction and velocity, atmospheric pressure and humidity etc. in the Kathmandu valley, that appears to play a crucial role in the dispersal of the pollutants.

Using pollution rose plots, we visualised CO and PM2.5 concentrations together with wind direction between 5-20 March and 21 March 21 – 5 April, respectively. Our analysis revealed that the frequency of winds from the southern direction increased during the fortnight of escalating fire outbreaks, coupled with a rise in the percentage of calm conditions from 10% to 15%, respectively. In tandem, both average CO and PM2.5 concentrations in the valley’s air increased by 64% (from 0.49 ppm between 5-20 March 5 to 0.82 ppm between 21 March and 5 April) and 47% (from 65.94 µgm-³ between 5-20 March to 97.2 µgm-³ between 21 March and 5 April), respectively (see Figs. 4 and 5).

Simultaneously, we used the hybrid single-particle Lagrangian integrated trajectory (HYSPLIT) model - a standard tool for simulating transport and dispersion of air pollutants – to track the source and movement of emissions to the valley during the severe pollution days, during the forest fire period.

A 48-hour backward trajectory analysis for identifying the sources of the emissions influencing daily air quality at the receptor location indicated that during the most polluted days pollutant sources showed higher likelihood of association with locations in the west/southwest of the valley where the forest fires were spatially concentrated.

The 48-hour backward trajectory for March 8, one of the days of relatively lower PM2.5 concentration in our month-long monitoring phase, traced incoming winds mainly from south/southeast sides of the valley. In contrast, the trajectory for 2 April, when high PM2.5 concentration was detected in the receptor location air, traced incoming winds from the forest fire prone western / southwest sides of the valley (Fig 6 top panels).

The findings from a 120-hour backward trajectory analysis for the frequency of airmass trajectories from long-distance emission sources are consistent with the surface wind patterns traced by the 48-hour back trajectories, thereby corroborating with long-range transport of emissions to the Kathmandu valley from distant sources, during severe forest fire episodes.

The 120-hour trajectory analysis, during the coinciding peak phases of pollution and forest fires, revealed higher frequency of incoming air masses from fire-affected regions outside of the valley, and hence higher likelihood of long-range transport of pollutants in the valley. In contrast, the pre-peak-fire period analysis showed higher frequency of surface winds that are more likely to bring in localised pollutants (Fig 6, bottom panels).

Bhutan’s agriculture sector – one that employs 40% of the population - is confronted with significant climate-related challenges visible in terms of change in rainfall patterns and fast drying up of spring water sources (UNDP, 2023)[1]. Owing to this and other structural challenges, the sector’s contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been steadily declining, threatening the country’s self-sufficiency in staple crops.

In Bhutan’s 13th Five Year Pan (13 FYP), agriculture and livestock sector are prioritised as one of the growth drivers to enhance food and nutrition security, elevate farmers’ income, and increase the sector’s contribution to GDP by investing in improving irrigation and water supply through innovative solutions to improve farm productivity. However, only 20% of cultivable land is irrigated, highlighting a critical gap in agricultural productivity. Only a small portion is effectively utilised, primarily through outdated, open-channel, gravity-fed systems. These are highly vulnerable to climate variability, resulting in reduced crop yields, more fallow land, and increased reliance on food imports. The country’s mountainous terrain further complicates irrigation, often requiring water to be lifted from rivers at lower elevations to fields at higher altitudes – an energy-intensive and logistically complex task.

Given Bhutan’s abundant green energy resource, expanding irrigation and water supply infrastructure by harnessing renewable energy (RE)-powered irrigation solutions, supported by a solid governance structure and mechanism reflecting the local context, could play a transformative role in addressing these challenges. By using renewable energy solutions, for e.g. Solar photovoltaic (PV) systems to pump water uphill, Bhutan can ensure year-round, reliable irrigation and water access, reduce labour burdens, especially on women, and enhance food security, income, and climate resilience. Further, deployment of RE-powered lift systems can potentially address drinking water challenges with appropriate treatments. It’s a game-changing intersection of technology, equity, and sustainability.

Integrating renewable energy (RE)-powered lift irrigation systems into non-energy sectors such as agriculture requires strong collaboration and engagement across multiple agencies. These solutions are inherently complex and demand a comprehensive understanding of various interrelated factors – including supportive policies and regulations, the energy supply-demand landscape, hydrology and precipitation patterns, river systems, socio-economic and cultural contexts, climatic variability, performance of water supply systems, agricultural practices, electro-mechanical systems, market dynamics, market access, and environmental risks. In essence, it is a multidisciplinary endeavour that requires a coordinated and cross-sectoral approach.

Taking RE-powered irrigation solutions to a large scale – whether for agriculture or public water supply – further amplifies the complexity due to the involvement of multiple institutions with either diverse or overlapping mandates and governance demands.

To address this and guide the development of an integrated approach to mainstream the uptake of RE-powered lift irrigation in Bhutan, a project advisory committee (PAC) was established through the WERELIS–Bhutan project (Women Empowerment through Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Powered Decentralised Lift Irrigation Systems) supported by Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC). Chaired by the director general of the Department of Energy, Royal Government of Bhutan, the seven-member committee includes senior-level representatives from the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Water, the Department of Infrastructure Development, the Bhutan Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and ICIMOD. This committee provides strategic guidance and oversight for implementing RE-powered lift irrigation systems, such as the WERELIS Project, and ensures the development of an enabling cross-sectoral approach.

"Every agency has its own mandate, policy, and planning framework. The biggest challenge is the fragmentation of responsibilities and accountability. More often than not, this leads to bottlenecks in implementation. The PAC is a critical mechanism that can bridge these institutional silos"

states Karma Penjor Dorji, Director General, Department of Energy, Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, Bhutan

On 23 May 2025, the Project Advisory Committee (PAC) members visited the Thosne Khola rural solar drinking water project site at Konjyosom Rural Municipality, Lalitpur, Nepal implemented by Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC), Government of Nepal.

During the visit, the Bhutanese delegation explored how solar power is being effectively utilised in addressing community water supply systems in Nepal’s mid-hills. The team examined technical specifications and financing mechanisms that could inform similar implementations back home. The site visit aimed to showcase the potential of renewable energy solutions in addressing water challenges in Bhutan, both for drinking and irrigation, as a part of climate change adaptation efforts.

“The first thing that struck me about the irrigation system here is the dynamic head[2]. It’s about 400 metres, which is a significant height. That’s huge. In Bhutan, we have one irrigation system with a dynamic head of about 150 metres, and even with that, we’re still struggling to pump water effectively. It becomes technically challenging and economically unfeasible.

But after seeing the lift irrigation system here, I was impressed by how simple and efficient it is. Despite the large dynamic head, they’re able to pump water and integrate the system for both irrigation and drinking water supply.

Another thing that stood out to me was the community’s contribution to the project. I learned that the total cost was about 21 million NPR, and around 2 million of that came from the community itself. That’s a great initiative – when the community invests their own resources, especially money, it gives them a sense of ownership and responsibility towards the system,” shares Tenzin Drugyel, National focal point for irrigation, Department of Agriculture, Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, Bhutan.

“The moment I saw this project site, I was immediately reminded of two locations in the east and two in the west of Bhutan where similar opportunities exist. There are many water bodies down in the gullies that can be harnessed and lifted to settlements on the mountain tops where people reside,” remarked Khandu Tshering, Principal Engineer, Irrigation Division, Department of Infrastructure Development, Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, Bhutan. “This project demonstrates proven renewable energy solutions that are technically sound, financially feasible, and hold strong potential for replication across Bhutan – provided there is effective coordination, integration, and support in design and financing mechanisms.”

“This field visit has been very enriching, especially because Bhutan and Nepal share similar geomorphological conditions. We are both dealing with the complexities of mountain ecosystems – steep terrain, high mountains, and deep valleys,” shared Kinzang Namgay, Deputy Chief Program Officer at the Department of Water, Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, Bhutan. “In such landscapes, solar-powered lift irrigation presents an important alternative for delivering water to rural communities living on mountain slopes. The project implemented here is highly replicable in Bhutan. If it works in Nepal, I believe it can work in Bhutan as well.” shares Kinzang Namgay, Deputy Chief Program Officer, Department of Water, Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, Bhutan.

“There are three key takeaways from today’s visit,” reflects Karma Penjor Dorji, Director General, Department of Energy, Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, Bhutan. “First is community engagement. When communities are involved right from the beginning of the project, we see better care and maintenance of the infrastructure, especially when ownership is transferred to them.

Second is capacity building. With proper training, communities can handle minor operations and maintenance issues on their own. This not only empowers them but also plays a critical role in the long-term sustainability of such projects.

Third is the importance of appropriate technology. We often design overly complex systems, and when the technology fails, the entire project can collapse. The technology should serve the community, not the other way around. Sustainability must be embedded as much in governance and community empowerment as it is in infrastructure, and in this scheme, I can clearly see these aspects being addressed.”

In Bhutan, the adoption of new technologies is guided by the country’s development philosophy of Gross National Happiness (GNH), which emphasises sustainable, inclusive, and holistic growth. In the energy sector, this translates into a strong commitment to green and clean energy solutions. As Bhutan seeks to revitalise its agriculture sector and improve access to water amidst growing climate challenges, renewable energy-powered lift irrigation presents a viable and context-appropriate solution.

The project implemented in Thosne Khola, Nepal, offers valuable lessons on how such systems can be effectively utilised for both irrigation and drinking water supply. With strong cross-sectoral collaboration and context-specific adaptation, Bhutan is well-positioned to replicate and scale these innovations. Doing so will not only enhance water security and strengthen rural livelihoods but also contribute significantly to long-term climate resilience .

[1] United Nations Development Programme. Assessment of Climate Risks on Water Resources for National Adaptation Plan. UNDP Bhutan, 8 November 2023. https://www.undp.org/bhutan/publications/assessment-climate-risks-water-resources-national-adaptation-plan

[2] height that the water needs to be lifted from the source (like a river or well) up to where it’s used (like a tank or field).

Meteorological agencies across the world have predicted a high probability of a wetter-and-hotter-than-normal summer monsoon for most of South Asia in 2025. That is likely to intensify the risks of water-related disasters in the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) terrain spread across the eight South Asian countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – surmise experts from the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) in their HKH Monsoon Outlook 2025.

The summer monsoon, between June and September, is the major source of precipitation in the HKH region with significant impacts on the hydrology of its river basins, which form the lifeline of nearly two billion people in the region. While a good monsoon is essential for replenishing these river systems, above-normal precipitations can expose the region to high risks of disastrous flash floods and landslides along the mountainous terrains and riverine floods in the plains. Historical records of floods in the region show that 72.5% of the total number of flood events recorded between 1980 and 2024 occurred during the summer monsoon season.

On the other hand, rising temperatures can accelerate cryosphere melting, contributing to short-term increases in river flow or ‘discharge’ and heightening the risk of glacial lake outburst floods, and in combination with wetter monsoon can enhance heat stress and cause waterborne disease outbreaks.

Pooling together the analyses of global and regional meteorological bodies like the 31st South Asian Climate Outlook Forum (SASCOF-31), APEC climate center (APCC), International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI), Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), along with those from various national agencies, the Outlook predicts temperature at above-normal level in almost all eight countries with an estimated mean summer temperature anomaly ranging from 0.5°C to 2°C above-normal. High probability of above-normal precipitations is predicted for over most of India, Nepal and Pakistan. While Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Myanmar are likely to receive near-normal levels of rainfall, normal to above-normal precipitations are also predicted for the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) of China.

Reflecting on these predictions, Arun Bhakta Shrestha, Senior Advisor at ICIMOD, reasserted the exacerbating vulnerability of the HKH region to increasing climate anomalies and cascading climate-induced disasters, “The tragic loss of lives and extensive damage during the September 2024 floods in Kathmandu Valley is a stark reminder of the rising climate threats in the region. It is a slice of the future staring us in the face. With projections across –the board indicating increasing monsoon precipitations and a shift toward more extreme events, there is an urgent need to revamp disaster preparedness and invest in improved forecasting and impact-based early warning systems across the region.”

Extreme weather events happen on the scale of a single day, while the nature, magnitude and extent of their adverse effects vary widely over physiography and across socioeconomic groups. Forecasting these events with accuracy calls for spatially and temporally localised signals of climatic anomalies. Simultaneously, such forecasts also need to account for exposure and/or vulnerability, translating the physical hazard characteristics into socioeconomic consequences.

However, given the dual dearth of short-term meteorological prediction capability and commensurate investments in the HKH, longer-term forecasts, such as the ones compiled in the HKH Monsoon Outlook, are critical for building insights into the prospective seasonal conditions at large. According to Sarthak Shrestha, Remote Sensing and Geo-Information Associate at ICIMOD, “Sharing this information timely is important from the point of disaster preparedness. Last year’s floods and landslides were an eye-opener for the strong need for early action and coordinated response across the region.”

In view of the rising frequency and aggravating severity of extreme weather events in the region, there is a growing consensus among regional meteorologists and disaster risk management experts on the need for impact-based forecasting of meteorological parameters and events. In tandem, ICIMOD has developed a suite of toolkits for forecasting precipitation, temperature, and river discharge up to two to ten days in advance, for Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal and Pakistan.

“These tools are already being used by the hydro-meteorological departments of the governments of Bangladesh and Nepalto generate their flood bulletins. The Red Cross and several municipalities across Nepal use these bulletins for anticipatory actions. The Benighat Rorang Municipality in the Bagmati Province of Nepal, for example, used these early warnings during the September 2024 floods to close schools in advance and keep almost 17,000 students safe. Our next step is to use these tools for impact-based forecasting,” says Manish Shrestha, Hydrologist at ICIMOD.

According to Saswata Sanyal, Manager, Disaster Risk Reduction Intervention, ICIMOD, “Our Community-Based Flood Early Warning Systems (CBFEWS) have proven to be life-saving tools, particularly in Nepal’s southern plains, where municipalities have adopted them to strengthen flood response. The demonstrated success of these systems has attracted interest from neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh, Bhutan, and India, to test and replicate similar approaches in their watersheds toward end-to-end warning and last-mile connectivity. This underscores the vital role of proactive, community-centered approaches in building resilience to climate-induced disasters. At ICIMOD, we aim at converting warnings to actions – empowering communities before the disaster strikes.”

Excellencies, distinguished delegates, colleagues,

It is an honour to represent the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development — ICIMOD — at this High-Level Conference on Glacier Preservation. We extend our sincere thanks to the Government of Tajikistan for their warm hospitality and commend their leadership – alongside the many countries and organisations represented here - in bringing global attention to this urgent and escalating crisis.

ICIMOD serves eight Regional Member Countries that span the vast expanse that is the Hindu Kush Himalaya — Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Pakistan, and is headquartered and hosted by the Government of Nepal in Kathmandu. Often called the Third Pole, this region holds the largest ice reserves outside the Arctic and Antarctic. It is home to over 240 million people and supports water, food, and energy security for more than 2 billion people downstream.

Yet the cryosphere here – as we have heard from so many delegates already - is degrading at alarming rates, due to warming, unsustainable development, and environmental degradation. Even under the most optimistic emissions scenarios, up to two-thirds of glacier volume could be lost by 2100. Peak water is projected around mid-century—just 25 years from now—after which flows will decline. The implications of these changes for regional – even global - stability are unthinkable.

Over 200 glacial lakes are now classified as potentially dangerous—particularly in Nepal, Bhutan, northern India, and Pakistan—posing serious risks to lives and infrastructure. These are no longer future threats. The science is clear. But the response is still far too limited.

At ICIMOD, we know no single country can address this alone. Glaciers cross borders!

That is why – at ICIMOD - we work regionally to generate evidence, support decisions, and enable action. But we need stronger collaboration and far greater investment.

We urge prioritisation in five areas:

1. On Science and Risk Assessment

2. On Inclusive Adaptation and Resilient Infrastructure

3. On Community Engagement and Indigenous Knowledge

4. On Policy Integration

5. On Regional and International Cooperation

The time for fragmented, reactive action is over. We must shift:

The HKH is critical to the stability and resilience of a large part of the world. Glacier preservation is not just an environmental concern—it is a core economic development issue.

ICIMOD stands ready to work with you all—to act decisively, at scale, and with the urgency this crisis demands.

In an era where artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being leveraged to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), digital tools hold immense potential for development initiatives. However, in rural areas with limited internet access, AI-based solutions might seem unachievable.

Gathering insights from communities is vital to understand their water needs. The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and Frank Water collaborated to conduct household surveys in two springshed sites in Nepal’s Kavrepalanchowk district (Opi and Bhelwati) using Frank Water’s Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Connect tool. Alongside these surveys, a pilot initiative by Colectiv, Frank Water, and ICIMOD tested the feasibility of collecting qualitative data through voice notes. This method aimed to assess the feasibility and efficiency gains from using AI to assist with transcription, translation, and analysis of qualitative data.

This case study highlights how a hybrid approach combining offline data collection with AI-supported analysis can enhance qualitative research in remote regions.

Community resource persons conducted 31 interviews with local householders, asking two key questions:

Challenges in water access: Can you tell me about any problems or difficulties you face in accessing clean drinking water? Would you like to make any changes to your drinking water source? (सफा पिउने पानी प्राप्त गर्न तपाईंले भोग्नु भएका कुनै समस्या वा कठिनाइहरूबारे भन्न सक्नुहुन्छ? के तपाईं आफ्नो पिउने पानीको स्रोतमा कुनै परिवर्तन गर्न चाहनुहुन्छ?)

Community resource persons recorded participants' responses as audio notes using mobile phones. The files were anonymised, uploaded to an encrypted online folder, and later transcribed, translated and analysed using Colectiv’s AI-based qualitative analysis tool.

Feasibility and challenges

What did the community say?

Community members had a strong preference for drinking spring water. Spring water tastes sweet and good, and people feel it is healthy and good.

म ओपी मूलको पानी पिउँछु। म जन्मेदेखि नै यही पानी पिइरहेको छु। यो पानी मलाई एकदमै स्वादिलो लाग्छ। यो नै सबैभन्दा राम्रो पानी हो किनभने यो अत्यन्तै मिठो छ । यो पानी एकपटक पिएपछि अरू कुनै पानी पिउन मन लाग्दैन। (I drink water from Opi spring, I've been drinking it since birth, it feels good, it's the best water because it's incredibly sweet. Once you drink it, you do not feel like drinking any other water)

Tap water and stored tank water were alternatives for a few people, but many avoided these sources. They use this water only for livestock or washing.

हाम्रो बोरिङ पनि छ, तर बोरिङको पानी पिउनको लागि त्यति योग्य छैन।लुगा धुन, भाडा मोल्न मात्र प्रयोग गर्ने गरिएको छ। (The water from our boring well is not as suitable, and it is only good for washing clothes and utensils.)

The main challenges they face are that the spring source can be far away and, especially in the rainy season, paths can become slippery and impassable. The spring can also get contaminated with overflowing water.

बर्खामा बाटो चिप्लो हुन्छ र हिउँदमाआफूलाईचाहिएकोजति पानी पाइदैन। (During the rainy season, the paths get slippery, and sometimes it's not easy to get as much water as wanted in winter season.)

बर्खामा मूलको पानी धमिलो हुन्छ, कहिलेकाहीँ किराफट्याङ्ग्रा पनि जम्मा हुन्छन्, र सफा पानी पाउने कुनै सम्भावना हुँदैन। (During the rainy season, it becomes muddy, sometimes insects accumulate, and there’s no way to get clean water)

People wanted improvements in infrastructures to help them have better drinking water access. Many people requested that their preferred spring water be brought closer to their homes to reduce the burden of collecting it. If the water could be piped directly to households, or at least to nearby tanks or reservoirs, it would help avoid the difficulties of collecting water along muddy paths.

ट्यांकी बनाइदिएर धारो जडान गरिदिए सजिलो हुन्थ्यो।बूढाबुढी बारम्बार पानी ल्याएर खान सक्दैनन्। (If a tank is built or a tap is provided it would be much easier. Elderly people can’t keep carrying water back and forth)

हरेक घरमा धारो जडान गरिदिए कस्तो सजिलो हुने थियो, मलाई त यस्तै लाग्छ! (If taps could be provided at every house, it would be convenient, that's what I feel)

Others requested improvements to existing sources, such as better pathways and protective measures to prevent contamination and overflow.

पानी नपस्ने गरी अलिकति ढलानसहित पर्खाल बनाउने र सम्भव भएमा वरिपरीको भुइँ पनि ढलान गरेर ढोकाहाल्नसके अझ राम्रो र सुरक्षित हुने थियो। (It would be better and safer to construct a wall with a slight slope so that water doesn't enter, and if possible, to install a door with the surrounding ground sloped accordingly.)

पँधेरोमा जाने बाटोअलि राम्रो बनाइदिनु पर्छ।पँधेरो वरिपरी खनेर आसपासको क्षेत्र अलिकति ठूलो बनाइदिनु पर्छ र राम्रोसँग संरक्षण गरिनुपर्छ। (It would help if the roads were improved. The area around the source needs to be a little bigger and better maintained)

As a partnership, we reflected on the inclusion of an AI tool for data collection and remote analysis. The process of solving development problems in remote regions across world has always meant involving ‘people from outside’ these communities. How much ever one may try – it’s difficult to bridge the gap between what is communicated by communities and what is understood by the ‘people from outside.’ The use of a tool like Colectiv reduces the communication gap drastically as the interpretation of what is spoken does not lie with individuals recording their responses, or in the reduction to survey items. Instead, this tool allowed all the subjective answers community members provided to be recorded verbatim without any interpretation and shows (qualitatively and quantitatively) what the community members want across various demographics within the community. We feel that needs assessment and understanding of community perceptions from such tools is closer to what the community means and not what is in the heads of interpreters, or those selected involved in the project.

This pilot demonstrated that AI-driven transcription and translation can support qualitative data collection in remote communities. In this case, human oversight was important for accuracy, but this may be less essential in other contexts. More broadly, the use of voice notes enabled researchers to capture community-driven narratives, providing valuable insights beyond quantitative survey responses.

By combining digital tools with human-centered approaches, organisations like ICIMOD, Frank Water and Colectiv can enhance development outcomes by ensuring that community perspectives can be used to improve programme planning and delivery. The value of a household survey can be greatly increased by adding tools that gather peoples’ voices and put them at the heart of decision-making.

The tourist season is at its peak in the hill stations and high mountains across the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) region as the scorching summer unfolds its arms. I remember last year, just as the snow was melting and summer was beginning, my colleagues and I were trekking to Laya – the highest settlement in Bhutan at an altitude of 3,800 metres above sea level (masl). Laya lies within the Jigme Dorji National Park, the country’s second largest park, situated in Gasa Dzongkhag, northwestern Bhutan. We drove from Thimphu via Gasa up to Tongchudrak where the road ends. We started the rest of the journey by foot.

I was very excited as we passed through the scenic beauty of natural and cultural manifestations. However, I was also quite surprised to see scattered plastic waste that people had left behind along the walking trails, even in such a remote and otherwise pristine place. When we asked our guide about it, he explained that the litter is mostly caused by local tourists and residents. Over time, their eating habits have changed, with growing consumption of packaged food and beverages, resulting in an increase in plastic waste in the area.

It was disheartening to see the mountain landscape marred by scattered multi-layered plastic wrappers, bottles made of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) and heaps of glass bottles. Along the trails, there were small open pits which had been dug for waste disposal, but they were often left exposed, with trash blown away by the wind. In some of these open pits, I also saw trash being openly burned. Just before we entered the village, there was a huge pile of mixed degradable and non-degradable waste dumped beside the river. I said to myself that I must at least collect the waste along the walking trails on my way back, which I decided to do.

Before leaving Laya, I obtained a couple of large sacks from a local shop owner. With one of my friends, I picked up single-use and multi-layered plastic wrappers (mostly from chocolates, chips, chewing gum, biscuits and other snacks), PET bottles, beer cans, and energy drink glass bottles scattered along the trails. As we collected the waste and walked down from Laya, the sack grew bigger and heavier; it was difficult to carry, but our determination did not waver. We brought back about 14 kilograms of waste just from the walking trail alone on our journey from Laya to Gasa. Most of the waste collected was PET bottles (e.g. soft drinks like Coke, Fanta, Pepsi) followed by beer cans, and juice tetra packs.

The above scenario resembles the fate of many other tourist destinations, religious sites and trekking routes across the HKH region. In our rapid assessment of solid waste management in high-mountain protected areas in Nepal, we found that almost 60% of the waste is biodegradable, which is often either fed to animals, buried, or used to make compost. Meanwhile, non-degradable waste is either openly dumped near rivers or burned, contaminating water sources and polluting the air, which directly or indirectly affects human health and biodiversity.

In the Indian Himalayan Region, the ‘Himalayan Cleanup’ campaign is a local movement that began in 2018 with the aim of addressing the waste crisis. The Himalayan Cleanup’s annual waste audit found over 75% of plastic waste collected in 2024 was non-recyclable.

In the HKH mountains, almost 45% to 60% of waste is degradable, while non-degradable waste accounts for a minimal quantity, and its effective recycling is always a challenge. Onsite waste recycling is not economically viable unless waste is aggregated. The aggregation and transportation of waste, particularly plastics and glass bottles from the mountains is very expensive. If the plastics are not compacted, transporting them to a recycling facility becomes very costly too. Likewise, handling and transporting glass bottles from mountainous terrain is very difficult, and at many places, heaps of such bottles are simply piled up and left. Transporting this waste is even more expensive due to the challenging geographical terrain and lack of motorable roads. However, in some places such as in the Everest and Annapurna regions of Nepal, local communities and hoteliers have voluntarily banned glass beer bottles, opting instead for aluminium cans which can be crushed before aggregation and then recycled.

Informal waste workers and rag pickers play a crucial role in waste collection and segregation for recycling, but there is a huge challenge in aligning them with a formal network and ensuring their occupational health and safety. In many cases, these informal workers are from outside the province or state and the local governments do not recognise their role for incentivisation.

Non-degradable waste should be further segregated based on type and characteristics. For example, a plastic soft drink bottle uses three distinct types of plastic – the bottle itself is made from Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET), the bottle cap is made of High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) and the label wrapper is made from Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE). PET and HDPE are highly valuable plastics and easily recyclable, whereas LDPE is characterised by low-density molecules, which is cheap to produce but not easily recycled. Single-use plastic bags, all kinds of packaging wrappers, coating on containers and bottles, and garbage bags are all LDPE plastics, whereas multilayered plastics have thin sheets of various other materials laminated together (including aluminium, plastics, and paper) and are difficult to separate.

LDPE and multilayered plastics are becoming a serious problem with rapid industrialisation and increased consumption of processed food resulting in consumers dumping these plastics all over the pristine mountain landscapes. Many recyclers do not use these plastics as the recovery process is difficult and costly.

As described in the situation in Laya, the dietary habits and consumption patterns of mountain people across the Himalayas are shifting towards processed and packaged foods. This has heightened the waste problems which are further exacerbated by inadequate infrastructure and lack of mountain-specific, simple and affordable waste management technologies. For example, sophisticated, modern and artificial intelligence (AI)-based waste management technologies available in the market, such as smart bins, waste-sorting robots, automatic high voltage bailer machines for waste compaction or even incinerators may not be suitable in the mountains unless they are portable, energy efficient, easily operated and maintained, and are customised to the local context depending on the waste characterisation and quantity.

The solutions to waste management should go beyond ‘end-of-life management’ – when a resource is no longer usable but could be recycled or upcycled towards a circular economy, whereby we can keep reusing the resources, creating a value from what could otherwise be considered waste. Here we outline some waste management solutions for the mountains:

Similarly, the local community-driven zero waste campaign, ‘The Himalayan Cleanup’ across the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR), is a clear example of a bottom-up approach to decentralised waste management and plastic recycling. In April 2025, several organisations across the IHR created the ‘Zero Waste Himalayan Alliance’ to tackle the reported 80% of single-use plastics from food and beverage packaging.

A World Bank report on solid waste management from 2018 projected that global waste generation is expected to rise 3.40 billion tonnes annually by 2050, a drastic increase from the current 2.01 billion tonnes. To curb this scenario and to bring systemic changes to effective waste management, our efforts should be threefold:

In addition, there should be:

There is still hope as we strive to maintain and protect cleaner and greener surroundings where our future generations can thrive healthily and coexist with nature. To mark this World Environment Day 2025, let us promise to #BeatPlasticPollution, let us nurture our mother Earth and let us serve the majestic Himalayas to sustain its crucial ecosystem services flows.

Acknowledgement

Sabitri Dhakal

Gillian Summers

Barsha Rani Gurung

Samuel Thomas

It is incredibly sad to learn that Professor U Shankar is no longer with us. He has been a great inspiration to many of us involved in teaching and research in economics in India, particularly in environmental economics, econometrics, and public policy. He provided invaluable support throughout his career. Professor Shankar’s academic achievements are truly impressive. He studied Economics at the Madras University and Annamalai University in Tamil Nadu, one of the states in India, in the 1950s. He completed his Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in econometrics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the United States of America (USA), in 1967.

Professor Shankar taught at the University of Wisconsin, USA, during the 1970s and became a full professor there in 1976. He later returned to India, where he played a key role in establishing the Department of Econometrics at the University of Madras in 1978. He became the President of the Indian Econometric Society in 1993. Prof. Sankar was one of the founders of the Madras School of Economics and became its director. He served as the National Program Coordinator for the World Bank-funded Environmental Capacity Building Program in India during the late 1990s. He was one of the main resource persons for this programme, which trained many young economists and administrators across India in Environmental Economics at that time. The programme brought a revolutionary change in the teaching and research methods in Environmental Economics in India, benefiting a generation of economists who specialised in this field. He also played a highly active role in a similar and significant programme in the broader context of South Asian countries – the South Asian Network for Development and Environmental Economics (SANDEE). In recognition of his valuable contributions to teaching and research in Environmental Economics, he was made a Fellow of SANDEE in 2009. Additionally, he was a National Fellow of the Indian Council of Social Science Research during the period 2003-2004.

In his illustrious career spanning several decades, Prof. Shankar published numerous articles in both national and international peer-reviewed journals. During the 1970s, he co-authored several papers in leading international journals, including The Review of Economic Studies (1969), International Economic Review (1970), The Review of Economics and Statistics (1973), Journal of Economic Theory (1977), among others. He also authored several books such as ‘Controlling Pollution: Incentives and Regulations,’ (with S Mehta and S Mundle, Sage Publications, Delhi, 1997), ‘Environmental Economics: Reader in Economics’ (Oxford University Press, Delhi, 2000), ‘Trade and Environment: A Study of India’s Leather Exports’ (Oxford University Press, 2006), and ‘The Economics of India’s Space Programme: An Exploratory Analysis’ (Oxford University Press, 2007).

In addition to his extensive scholarly contributions, Prof. Shankar was actively associated with various professional bodies, academic boards, and policy committees in India. His teaching at several universities and other academic institutions has benefited numerous students, many of whom now hold key positions in academia.

Imagine a world where every plant, animal, and insect are catalogued, and this is accessible to everyone through biodiversity data platforms. How would that affect our understanding of nature? Knowledge, after all, is our greatest weapon in the fight against biodiversity loss.

Over the past few months, as we explored biodiversity data from across the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH), we realised that open access biodiversity data platforms such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and its regional node, the Hindu Kush Himalayan Biodiversity Information Facility (HKHBIF), are much more than repositories of information on fauna, flora, and fungi. They are windows into the stunning diversity of life that allow us to explore the living organisms around us. These tools are open repositories for evidence-based decision-making in conservation actions which can inform and inspire action in ways that can change the world. One example of this is when these data are used as a supplement for IUCN Red List Assessments in preparing range maps, which is one of the criteria for categorising the conservation status of species.

This year, as the world celebrates the International Day for Biological Diversity (IDB) 2025, we want to approach open access biodiversity data platforms from the perspective of their role in achieving our global aspirations for biodiversity, climate, and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Since the UN General Assembly’s proclamation in December 2000, 22nd May has been the day to celebrate the diversity of life on this planet and our collective actions to protect it. The day marks the adoption of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) on 22nd May, 1992. Crucially, beyond a celebration, this day is a call to action - reminding us of what remains to be done.

How do open access biodiversity data platforms align with this year’s IDB theme: “Harmony with Nature and Sustainable Development”? This theme resonates deeply with the goals of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) and the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These two sets of goals are interconnected; we cannot achieve the SDGs without reversing biodiversity loss. Simultaneously, the way we frame our actions to achieve the SDGs can drive the change towards living in harmony with nature. This vision of interconnectedness reiterates the urgent need for integrated and transformative actions to secure a sustainable, fair, equitable, and resilient future for all, where the goals of the 2030 Agenda and the KMGBF are pursued in tandem.

Of the 23 action-oriented global targets of the KMGBF, the GBIF and HKHBIF directly align with and contribute to Target 21: Ensure That Knowledge Is Available and Accessible To Guide Biodiversity Action. This target is crucial. It recognises that we need the most reliable data, information, and knowledge in an open and usable format – to support decisions, policies, and awareness, and effective biodiversity governance and inclusive management.

The GBIF is a global network that provides open access biodiversity data from sources as diverse as herbarium and museum collections, camera traps, field observations, monitoring sites and citizen science platforms like eBird and iNaturalist. They use common standards like Darwin Core, which organise millions of species records on its platform, enabling their systematic accreditation and use. The data is shared openly under Creative Commons licenses, allowing researchers, scientists, and others to freely use the data for research and education. As of April 2025, GBIF hosts over 3 billion species occurrence records contributed by over 1,800 institutions globally. This data has been used in academia, policy and decision making, species extinction risk assessments, and habitat suitability mapping by local, national, and large-scale intergovernmental and conventional based bodies like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

HKHBIF, hosted by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), brings a regional lens to this effort. It focuses on collecting, sharing, and spreading biodiversity data from the HKH region, that hosts parts or all of four global biodiversity hotspots. With over 200,000 species records already published through GBIF, HKHBIF is our regional space to mobilise biodiversity data across ICIMOD’s eight Regional Member Countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan. From GBIF records, we found 3,874 species of birds, 1,339 mammals, 837 reptiles, 438 amphibians, 26,351 insects, 41,001 plants, and 14, 286 fungi within the HKH region.

Biodiversity data does not sit in isolation. It is crucial for achieving the UN SDGs, especially Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being), 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), Goal 10 (Reduced Inequality), Goal 13 (Climate Action), Goal 14 (Life Below Water), and Goal 15 (Life on Land). A study from the Chinese Academy of Sciences GBIF node shows how biodiversity data supports SDGs, such as Goal 10 in recognising rights, valuing biodiversity and related knowledge, and building an environment for equitable benefit sharing, and Goal 8 by linking biodiversity and sustainable livelihoods as a requirement for decent work and economic growth. Making biodiversity information available in the public domain, such as the publication of pictorial guidebooks on the region’s flora can aid in education and conservation efforts – contributing to Goals 4 and 15, respectively.

As we mark the International Day for Biological Diversity for the 25th time, let us recognise that platforms like GBIF and HKHBIF are more than data repositories. They are catalysts driving nature-positive actions to achieve both conservation and sustainable development outcomes. In the HKH, where biodiversity loss continues and remains less accounted for and measured – as highlighted in a Mongabay India commentary that biodiversity data from the region is poorly represented in GBIF and largely published by institutions outside the region — these platforms remind us of the power of collaboration, to bridge data gaps and amplify local voices in the global biodiversity discourse.

ICIMOD recently collaborated with GBIF and other biodiversity-mandated institutions in HKH countries such as the Zoological Survey of India, Forest Action Nepal, National Biodiversity Centre in Bhutan and National Science Library, Chinese Academy of Sciences to enhance the capacity of institutions on biodiversity data mobilisation from the HKH.

Our call to action emphasises greater investment for expanding open-access digital platforms of biodiversity data, strengthening institutional collaborations in building HKH biodiversity data repositories to highlight the status of mountain biodiversity, raising awareness on how such data platforms address the issue of intellectual property rights, and engaging and strengthening the capacity of citizen scientists to use such platforms.

By making biodiversity data openly accessible and easy to use, GBIF and HKHBIF serve as a bridge between the KMGBF and the SDGs. GBIF offers the global infrastructure needed to track KMGBF progress and monitor SDG indicators. HKHBIF contextualises this data for the HKH region, thereby supporting and motivating the HKH countries to translate global biodiversity goals into regional actions for biodiversity conversation and resilience, and in effect, find a space for the mountain voices in global biodiversity fora.

Nagaland in India’s northeast is rich in biocultural diversity, where the people have a notable aspect of connection to nature and wildlife, reflected by their cultural practices and beliefs. The Nagas’ culture and tradition, folklore and folksongs, taboos and myths express intimate relationships with the complexities of the ecological system. One example is the myth of the tattoo marks on the catfish, which are attributed to ichthyomorphosis, i.e. a human transformed into a fish.

As such, Nagaland is an exemplary case where the Constitution of India, under Article 371(A), provides special provisions for administration, and community ownership over land and natural resources. As one of India’s seven ‘sister states’, Nagaland is home to sixteen major tribes and exhibits legal pluralism within the state, with varying governance systems among different tribes.

At a global scale, the aim known as ‘30x30’ constitutes effectively conserving and managing at least 30% of terrestrial, inland water, and coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services – by 2030. This is Target 3 of the ‘Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’, adopted by 195 countries in 2022 at the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in Montreal, Canada.

Achieving Target 3 is considered by international scientists as the minimum action needed if humanity is to succeed in halting and reversing biodiversity decline by 2030. Experts also point to the significance of connectivity, effectiveness, and respecting and recognising the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPLCs) when carrying out conservation. In this way, the 30x30 target is imperative in Nagaland.

As forest dwellers, the socio-cultural, economic, and subsistence activities of the Nagas was traditionally dependent on the use of forest resources. However, over time, population pressure, deforestation and modernisation began to erode traditional forest management systems, leading to unchecked hunting and logging, and hence threatening biodiversity. In response to these challenges, communities started voluntarily designating portions of their lands as areas to conserve biodiversity. This long-standing cultural practice was later formalised and designated as Community Conserved Areas (CCAs) following the customary laws of the Naga people. The tribal councils, guided by customary laws, regulate hunting, fishing, and the use of forest resources.

CCAs in Nagaland have been in existence since the 1800s, when the tropical evergreen forest of Yingnyushang was declared as a CCA by Yongphang village in Longleng District. But the growth of CCAs as we know them today began during the 1980s. In 1998, the village of Khonoma in Nagaland initiated a community-led conservation project to protect the Blyth’s Tragopan (Tragopan blythii), a pheasant species that is categorised as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. The village banned hunting of the endangered Blyth’s Tragopan and other wildlife, and imposed fines for violations. Today, there are an estimated 432 CCAs, covering 59,661.23 hectares, voluntarily managed by the tribal peoples in Nagaland (NCCAF, 2025).

The CCA model offers a win-win situation for both people and nature. CCAs are led by the IPLCs through local customary laws to promote a traditional lifestyle, socio-cultural identity, spirituality, and livelihood (Kothari, 2006).

CCAs play a crucial role in preserving the rich biodiversity of Nagaland. Traditional practices like ‘jhum’ or shifting cultivation – which entails clearing a plot of land for agriculture and then leaving it to regenerate before shifting to a different plot – ensure the survival of successional species, thus increasing overall biodiversity metrics. It also prevents the forest stand from reaching the climax stage, maintaining species evenness and diversity. Another example is the alder-based farming practiced in Khonoma, which promotes sustainable land use by ameliorating soil fertility and providing livelihood resources simultaneously.

However, there are significant challenges to the sustainability of CCAs, as there is no sustainable financing mechanism for managing them. The ban on traditional hunting limiting resource use has also created stress and ambiguity among the people of Nagaland. Furthermore, the transmutation of CCAs into Community Reserves (CRs), a formal protected area, imposes similar restrictions on land use change and inherits certain rules that are applied in other protected areas (PAs) as per the Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Act 2002, 36A – 36D (Government of India, 2002). In simpler terms, once declared CRs, the government controls the use of resources and activity inside the community reserves.

To address these issues, CCAs in Nagaland require a different designation, such as ‘Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures’ (OECMs) so that they can continue to be managed as CCAs with support from the national and international community and gain clear recognition of the efforts of the community in conserving biological diversity at regional and global scales.

One promising solution to gather global attention and funding for the management of CCAs is the incorporation of CCAs as OECMs(IUCN-WCPA Task Force on OECMs, 2019; Hoffmann, 2022). OECM is defined as "a geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in-situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socio-economic, and other locally relevant values” (CBD, 2018). The state of Nagaland could potentially recognise all 52.07% of the state’s forests as OECMs (Forest Survey of India, 2023).