Nagaland in India’s northeast is rich in biocultural diversity, where the people have a notable aspect of connection to nature and wildlife, reflected by their cultural practices and beliefs. The Nagas’ culture and tradition, folklore and folksongs, taboos and myths express intimate relationships with the complexities of the ecological system. One example is the myth of the tattoo marks on the catfish, which are attributed to ichthyomorphosis, i.e. a human transformed into a fish.

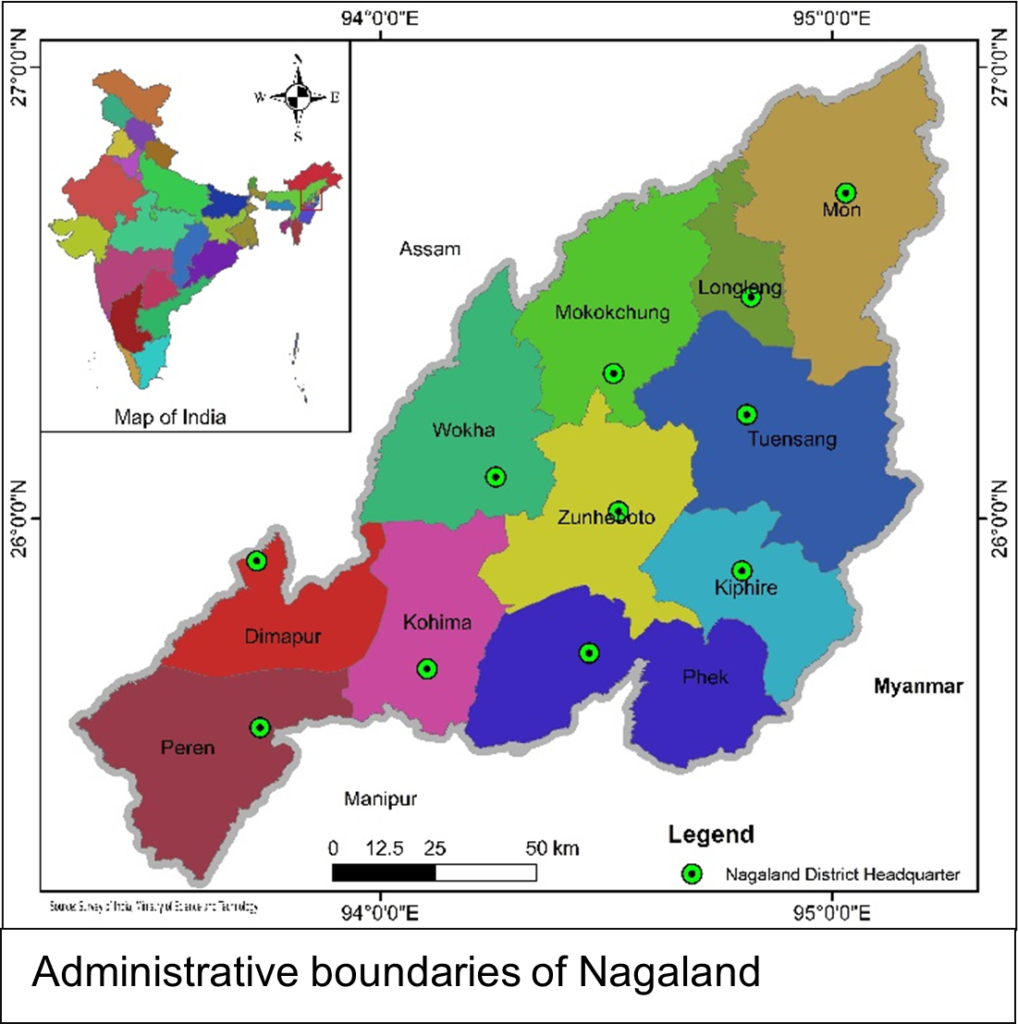

As such, Nagaland is an exemplary case where the Constitution of India, under Article 371(A), provides special provisions for administration, and community ownership over land and natural resources. As one of India’s seven ‘sister states’, Nagaland is home to sixteen major tribes and exhibits legal pluralism [1] within the state, with varying governance systems among different tribes.

At a global scale, the aim known as ‘30x30’ constitutes effectively conserving and managing at least 30% of terrestrial, inland water, and coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services – by 2030. This is Target 3 of the ‘Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’, adopted by 195 countries in 2022 at the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in Montreal, Canada.

Achieving Target 3 is considered by international scientists as the minimum action needed if humanity is to succeed in halting and reversing biodiversity decline by 2030. Experts also point to the significance of connectivity, effectiveness, and respecting and recognising the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPLCs) when carrying out conservation. In this way, the 30x30 target is imperative in Nagaland.

Nagaland: a unique case of community forest conservation

As forest dwellers, the socio-cultural, economic, and subsistence activities of the Nagas was traditionally dependent on the use of forest resources. However, over time, population pressure, deforestation and modernisation began to erode traditional forest management systems, leading to unchecked hunting and logging, and hence threatening biodiversity. In response to these challenges, communities started voluntarily designating portions of their lands as areas to conserve biodiversity. This long-standing cultural practice was later formalised and designated as Community Conserved Areas (CCAs) following the customary laws of the Naga people. The tribal councils, guided by customary laws, regulate hunting, fishing, and the use of forest resources.

CCAs in Nagaland have been in existence since the 1800s, when the tropical evergreen forest of Yingnyushang was declared as a CCA by Yongphang village [3] in Longleng District. But the growth of CCAs as we know them today began during the 1980s. In 1998, the village of Khonoma in Nagaland initiated a community-led conservation project to protect the Blyth’s Tragopan (Tragopan blythii), a pheasant species that is categorised as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. The village banned hunting of the endangered Blyth’s Tragopan and other wildlife, and imposed fines for violations. Today, there are an estimated 432 CCAs, covering 59,661.23 hectares, voluntarily managed by the tribal peoples in Nagaland (NCCAF, 2025 [4]).

CCAs – a win-win for people and nature

The CCA model offers a win-win situation for both people and nature. CCAs are led by the IPLCs through local customary laws to promote a traditional lifestyle, socio-cultural identity, spirituality, and livelihood (Kothari, 2006 [6]).

CCAs play a crucial role in preserving the rich biodiversity of Nagaland. Traditional practices like ‘jhum’ or shifting cultivation – which entails clearing a plot of land for agriculture and then leaving it to regenerate before shifting to a different plot – ensure the survival of successional species, thus increasing overall biodiversity metrics. It also prevents the forest stand from reaching the climax stage, maintaining species evenness and diversity. Another example is the alder-based farming practiced in Khonoma, which promotes sustainable land use by ameliorating soil fertility and providing livelihood resources simultaneously.

[7]

[7]However, there are significant challenges to the sustainability of CCAs, as there is no sustainable financing mechanism for managing them. The ban on traditional hunting limiting resource use has also created stress and ambiguity among the people of Nagaland. Furthermore, the transmutation of CCAs into Community Reserves (CRs), a formal protected area, imposes similar restrictions on land use change and inherits certain rules that are applied in other protected areas (PAs) as per the Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Act 2002, 36A – 36D (Government of India, 2002 [8]). In simpler terms, once declared CRs, the government controls the use of resources and activity inside the community reserves.

To address these issues, CCAs in Nagaland require a different designation, such as ‘Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures’ (OECMs [9]) so that they can continue to be managed as CCAs with support from the national and international community and gain clear recognition of the efforts of the community in conserving biological diversity at regional and global scales.

CCAs as OECMs – a prime opportunity?

One promising solution to gather global attention and funding for the management of CCAs is the incorporation of CCAs as OECMs(IUCN-WCPA Task Force on OECMs, 2019 [10]; Hoffmann, 2022 [11]). OECM is defined as "a geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in-situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socio-economic, and other locally relevant values” (CBD, 2018). The state of Nagaland could potentially recognise all 52.07% [12] of the state’s forests as OECMs (Forest Survey of India, 2023 [12]).

Even in other areas that are not considered forest, Nagaland holds tremendous potential for OECMs across agro-ecological landscapes such as jhum areas, alder-based farming systems, and the zabo system that support a great diversity of farmland-dependent species and related ecosystems. Zabo means ‘impounding of water’; this system integrates water harvesting and agriculture, where the rainfed water is collected and used in multilayers for domestic use, animal rearing and growing vegetables.

OECMs are often perceived to be synonymous with protected areas [13], but there are key differences. The primary objective of PAs is to achieve conservation outcomes (not excluding other related benefits), while the primary objectives of OECMs are not limited to conservation benefits, but include cultural preservation or other traditional purposes, and recognise diverse governance mechanisms, which align with the management of CCAs (Sharma et al., 2023 [14]). OECMs duly recognise and support IPLCs and their contribution to conserving local biodiversity (Jonas et al., 2021 [15]). The integration and adoption of OECMs into policy, planning, governance, and management of areas important for biodiversity can help achieve ambitious conservation goals like 30ᵡ30 [16], and ‘Nature needs half’ [17](Dudley et al., 2018 [18]) – an international coalition that advocates for the protection of at least half of the Earth’s land and oceans to ensure the health of ecosystems and biodiversity.

The table below summarises how CCAs in Nagaland align with OECM criteria (Table 1).

| OECM Criteria | How CCA is aligning with OECM Criteria |

|---|---|

| Area is not currently recognised as a protected area | CCAs, other than recognised as protected area by government of India, can be recognise as OECM. |

| Area is governed and managed | CCAs are generally outlined with traditional boundaries like natural structures by village clans and tribal people of Nagaland and are managed and governed by the existing customary laws. |

| Achieves sustained and effective contribution to in-situ conservation of biodiversity | CCAs are managed effectively in response to addressing existing or anticipated threats to deliver positive and sustained outcomes in-situ through voluntary effort. |

| Associated ecosystem functions and services and cultural, spiritual, socio-economic, and other locally relevant values | Traditional agricultural practices (jhum, alder-based), water and land management practices (paddy-cum-fish, Zabo), and religious sites (sacred groves) in the CCAs are inherent traditional practices embedded in the culture and livelihood of the people in Nagaland. |

[19]

[19]Policy support and gaps

The government of India has developed criteria and guidelines on identifying an OECM [20] in the country (MoEFCC, NBA & UNDP [20] 2022). The state-specific legislation, Nagaland Village and Area Councils Act, 1978 [21], empowers village councils to manage natural resources, providing a governance framework essential for OECM recognition.

Despite subsidiary provisions supporting the transition of CCAs to OECMs, challenges remain, such as overlapping mandates between customary and statutory law, and lack of specific legal frameworks for recognising CCAs as OECMs. Complicating this further, the state regards all the forests under community management as unclassified state forest, not only in Nagaland but also in neighbouring states like Arunachal Pradesh. Thus, if we are exploring CCAs as OECM, we are limited by the very first OECM criteria.

A second concern among communities is the loss of control with the change to OECM. They cite the case of transformation of CCA to community reserves (formal protected areas) which excludes them from claiming the OECM title. A third concern is the history of PA formation, exclusion of communities, and restrictions on their rights to access natural resources.

To understand more, we must dig deep into political ecology on how the benefit-sharing promises by the government to the real stewards are overshadowed and rights to resources are restricted.

These ambiguities in management and status of the CCAs as potential OECMs need to be resolved with new central and state-level policies that articulate rights and responsibilities clearly and don’t impinge on the rights and special status that communities enjoy in Nagaland.

This recognition requires multi-stakeholder dialogue between the Naga people, and state and national governments. This recognition also needs to be advocated through media campaigns, outlooks, and communication products to build awareness among policymakers and IPLCs about the benefits of implementing the OECMs and to design effective legal mechanisms for safeguarding the rights of communities in the transformation of CCAs to OECMs.

Overcoming challenges to recognise conservation stewardship

CCAs in Nagaland represent a powerful model of Indigenous-led conservation, deeply rooted in the cultural and spiritual practices of the local tribes. However, to ensure their sustainability and effectiveness, it is crucial to address the funding and legal ambiguities and challenges they face. By aligning CCAs with OECM criteria, we not only preserve biodiversity but also uphold the cultural and socio-economic values integral to the people of Nagaland and ensure recognition and reward for their conservation stewardship beyond the national scale. Community efforts in conserving and managing CCAs in Nagaland deserve special recognition nationally and globally.

Disclaimer: All views, statements, and opinions expressed in this blog are solely those of the authors. They are drawn from various articles and reports, and do not necessarily reflect the views of ICIMOD, including any statements regarding the legal status of any country, territory, city, or area, the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or the endorsement of any product.

Ramesh Kathariya is a Research Associate at ICIMOD

Supongnukshi Ao is the Chief Conservator of Forests & Member Secretary of the Nagaland State Biodiversity Board (NSBB)

Sunita Chaudhary is Biodiversity Lead at ICIMOD

References

CBD. (2018). Decision adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Convention on Biological Diversity. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-14/cop-14-dec-08-en.pdf

Dudley, N., Jonas, H., Nelson, F., Parrish, J., Pyhälä, A., Stolton, S., Watson, J. E. M. (2018). The essential role of other effective area-based conservation measures in achieving big bold conservation targets. Global Ecology and Conservation, 15, e00424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00424

Government of India. (2002). The Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Act, 2002. Retrieved from https://indiankanoon.org/doc/897686/

Hoffmann, S. (2022). Challenges and opportunities of area-based conservation in reaching biodiversity and sustainability goals. Biodiversity and Conservation, 31, 325–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-021-02340-2

Forest Survey of India. (2023). India State of Forest Report 2023, Volume 1. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India. Retrieved from https://fsi.nic.in/uploads/isfr2023/isfr_book_eng-vol-1_2023.pdf [12]

Imlinungla, S. (2023). Understanding the community conserved areas: Rediscovering the role of indigenous peoples. International Journal for Research Trends and Innovation, 8(5), 2233-2237. Retrieved from https://ijrti.org/papers/IJRTI2305222.pdf [3]

IUCN-WCPA Task Force on OECMs. (2019). Recognising and reporting other effective area-based conservation measures. IUCN. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2019.PATRS.3.en

Jonas, H., Ahmadia, G., Bingham, H., Briggs, J., Butchart, S., Cariño, J., Chassot, O., Chaudhary, S., Darling, E., DeGemmis, A., Dudley, N., Fa, J., Fitzsimons, J., Garnett, S., Geldmann, J., Golden Kroner, R., Gurney, G., Harrington, A., Himes‐Cornell, A., & Weizsäcker, C. (2021). Equitable and effective area‐based conservation: Towards the conserved areas paradigm. Parks, 27(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2021.PARKS‐27‐1HJ.en

Kothari, A. (2006). Community conserved areas: Towards ecological and livelihood security. PARKS, 16(1), 3–13. Retrieved from https://iucn.org/sites/default/files/import/downloads/parks_16_1_forweb.pdf

MoEFCC, NBA, & UNDP. (2022). Criteria and Guidelines for Identifying Other Effective Area Based Conservation Measures (OECMs) in India. Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, National Biodiversity Authority, United Nation Development Programme. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/india/publications/criteria-and-guidelines-identifying-oecms-india [20]

NCCAF. (2025). Nagaland CCA Forum. Community Conserved Areas South Asia. Retrieved on 10 February 2025 from https://nccaf.communityconservedareas.org/

Sharma, M., Pasha, M. K. S., Nightingale, M., & MacKinnon, K. (2023). Status of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) in Asia. Bangkok, Thailand: IUCN Asia Regional Office. Retrieved from https://iucn.org/sites/default/files/2023-11/status-of-oecms-in-asia-report-high-quality_compressed.pdf