Rising temperatures, prolonged droughts, and dry forests have doubled forest fire incidents in the past decade in Nepal with 2025 projected to be the worst year.

The seasonal reality of HKH air pollution

Air pollution remains one of the most persistent and pressing challenges in the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) region. The region is caught in a recurring cycle of toxic air, with pollution levels peaking twice a year, between October to November and from March to April. March–April pollution surge is largely driven by widespread forest fires, which have been increasing each year due to drier winters, creating a layer of tiny particles, obstructing the visibility called haze. This haze can be composed of various particles, including dust, smoke, aerosols, and smog. For the October–November period, the pollution spike is largely attributed to agricultural residue burning across the Indo Gangetic Plains (IGP) countries, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan, as farmers prepare their fields for the next cropping cycle. Although these burnings are localised, their effects are widespread, affecting the HKH region with adverse environmental, socio-economic, and health consequences.

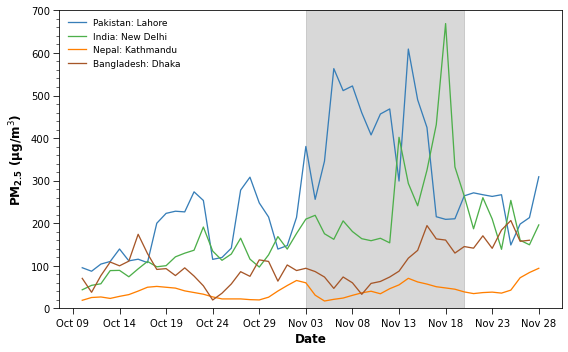

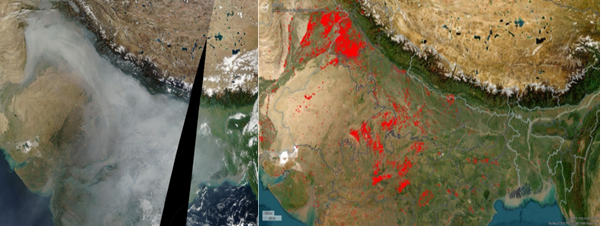

November 2024 recorded PM2.5 (particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometres or less) air pollutant concentrations exceeding 500 µg/m3 in Lahore, Pakistan, and New Delhi, India, as recorded by AirNow. Peak haze (slight obscuration of the lower atmosphere) and air pollution levels occurred in mid-November 2025, aligning with burning activity. The haze then moved eastward across the IGP, with rising PM2.5 concentrations in downstream cities. Dhaka, Bangladesh, recorded a noticeable rise in particulate pollution following November 12, indicating regional movement of the air pollutants. This spatial and temporal pattern confirms that the agricultural residue-driven haze events contribute to air pollution across the IGP region.

From the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) satellite imaging data, we can see how the haze over the region decreases as the crop burning period ends. In early November 2025, satellite data captured a thick haze spreading across the IGP. Between November 4 and 7, over 1,250 active fires were recorded, indicating widespread agricultural residue burning. The haze persisted through the month, peaking in intensity toward the end of November. Although cloud cover briefly masked the smoke in NASA imagery, the haze became visible again by the first week of December. As fire activity declined to just under 200 counts, visibility improved noticeably.

The pattern tells a clear story: more stubble (agricultural residue) burning leads to heavier haze. The data reinforce what is increasingly evident: agricultural fires are a major contributor to regional air pollution, with serious consequences for health and the environment.

Challenge with agricultural residue burning

In the broader context of climate change and air pollution impacts, it is unfair to highlight agricultural residue burning without acknowledging pollution from road traffic and industries. However, the challenge of agricultural residue burning persists and remains a significant contributor to air pollution. While its impact may be smaller compared to other sources, it is an issue that can be addressed through coordinated efforts involving the government, the private sector, and farmers.

Unfortunately, discussions on agricultural residue burning, air pollution, and health impacts often overlook the struggles of farmers. Farmers' continued reliance on burning stubble, particularly in the IGP, is driven by a complex interplay of cultural norms, economic constraints, labour shortages, and tight timelines between crop cycles. The practice of burning is perceived as a quick and cost-effective way to clear large volumes of agricultural residues for the next crop season. In most parts of the IGP, wheat is planted right after rice is harvested, within approximately 20 days.

Stubble burning persists due to several challenges, including limited awareness among farmers about its environmental and health impacts, and the widespread myth that burning returns nutrients to the soil. While subsidies exist, tools like straw choppers and balers remain costly and out of reach for many small-scale farmers. Weak market linkages for stubble, especially paddy straw, further reduce motivation for sustainable management. The transitions to alternatives for agricultural residue burning remain hindered by inadequate and fragmented policy support, particularly limited financial incentives and weak market development are making adoption difficult for farmers and stakeholders.

Innovative pathways to manage crop residue

There are promising solutions, such as affordable residue management technologies to policy innovations and community-led initiatives that are showing real potential to reduce stubble burning and improve air quality.

The innovative approach of turning agricultural residue into pellets is emerging as an ambitious alternative to burning fossil fuels, creating more green jobs, improving soil health and air quality, and a home-grown economy resulting in lesser dependency on fossil fuel imports. Converting the paddy stubble into high-density pellets reduces agricultural residue burning and helps in combating the associated air pollution by substituting fossil fuel in the industries, which further thrives the clean and green environment. The integration of agricultural residues into the energy matrix can enhance energy security and diversification of energy sources. As global energy demands increase, the reliance on traditional energy sources can pose risks to energy security.

While pelletisation is promising, there are challenges, such as transportation and storage costs, and availability of pelletisation facilities. Besides, only a handful of machinery is deployed at available pelletisation facilities, so not all farmers have access to such machinery. These factors contribute to farmers' hesitation to adopt pelleting, despite awareness.

There are also other sustainable agricultural residue management practices where agricultural residues are left in the field to naturally decompose, which improves soil health and fertility over time. Unlike burning, this approach reduces environmental pollution and enhances productivity through methods like mulching, no-till farming, and crop rotation. This approach is encouraged as studies show they can boost cereal grain yields by up to 37% and significantly cut soil erosion and carbon emissions. However, adoption remains limited due to low farmer awareness, lack of machinery access, and competing uses for residues such as livestock fodder.

Biochar is the other promising ex-situ solution for managing agricultural residue, where biomass residue is converted into carbon-rich materials to use as fertiliser in the field. This addresses the residue disposal issue while improving soil fertility, productivity, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Studies show biochar can increase average yields by 11% and cut 12% of human-induced emissions annually. However, high production costs and variable performance limit widespread adoption. Collaborations with research institutions and international bodies, along with strong policy support, are essential to improve production standards, build capacity, and make biochar a viable tool for sustainable agriculture and climate action.

Optimising market linkages

Scaling up the agricultural residue management solutions will require government support to get them off the ground. The issue of low supply of the paddy straw stubble used in the productive sector is addressed through the awareness and capacity building of farmers, but the effort is insufficient. Thus, IGP countries' strict regulations, such as mandatory enforcement of agro residue-based biomass pellets in the co-firing, and 7–20% use in thermal power plants and brick kilns could advance the scaling up of pelletisation. This enforcement would create significant market demand for the paddy straw pellets, attracting interested investors to get engaged in the paddy straw-based pellet production.

What could the future look like?

Managing agricultural residue needs to be heavily subsidised to offset related costs. Countries in the IGP are increasingly opting for strict rules to control open agricultural residue burning. In India, the open burning of agricultural residue can be reported as a crime. With farmers facing threats of fines and imprisonment, it has become almost impossible to engage in constructive dialogue, and it has further alienated the farming community. A more effective approach to rewarding farmers for not burning agricultural residue can foster collaboration and cooperation.

Control agricultural residue burning and solving the smog and haze problem will require putting farmers at the centre of the conversation. Innovation and policy commitment, along with strong monitoring tools, are the keys to cleaner air and a healthier environment.

Understanding and addressing farmers’ challenges is only the beginning. The available solutions are showing promise in addressing the current haze crisis, but these are not standalone or long-term solutions. The need to invest in research and development to explore more sustainable alternatives is ever pressing. Long-term solutions must address the cause, and not just manage symptoms.